I am very interested in how bodies behave in space, be they galaxies, stars, planets, dwarf planets, moons or spacecraft. The fascination comes mostly from my interest in human spaceflight, and in how surprising the mechanics turn out to be once one starts learning about it, and also due the awe that arises in learning that spaceflight–be it natural, and exhibited by natural objects, like those mentioned above, or unnatural, and done by human beings–involves the natural, predictable, controllable (in human cases) and dynamic relationships that occur between masses in space–called orbits.

From the outside, orbital mechanics looks difficult to understand–and it is, which is why I only have apprehended the basics–but the average person can understand the basic principles, which, as I alluded to before, become much more fascinating once the non-initiated person begins to see, that, for example–sending a spacecraft aloft and into orbit–specifically–is amazingly much more surprising and complex than simply pointing a rocket at the sky and firing its engines.

“What goes up,

must come down”, goes the song, but what if we don’t want to come down right away, and moreover, we don’t want to kill anyone in the process, including those who may be inside our spacecraft–namely ourselves–how do we keep ourselves or our spacecraft up there?

Getting into space–into orbit, that is–is not as simple as escaping the Earth’s gravity, because, unless we want to stay out there for a very long time, like, basically forever, orbiting the sun until we die, and we are not headed to the moon or another planet or another planet’s moon–we must manage Earth’s gravity, because… it is Earth’s gravity (or, actually, the attraction between Earth’s mass and that of our spaceship) that keeps us and our spaceship in orbit.…

So–in the end, one wants to go up… and wants to let the “coming down” force of “what comes down” keep our spacecraft… up—there. Does this sound strange? Then there are all sorts of details about velocity (speed + direction), the direction and amount of power we use to fire our engines, with which we go up and down, the shape of the orbit we circumscribe and want to remain in and, then descend or transfer from, and how that changes our altitude–which changes your speed, as well–and… so on.

© Copyright 2017 – 2025 Carl Atteniese / All rights reserved

In only one Star Trek episode–in the old days–did I hear Captain Kirk talk about the apogee of the Enterprise’s orbit–the point which is the farthest distance in the orbit from the parent body (the celestial body which our craft–or a moon–or other satellite–is orbiting), which is opposite the perigee, or the closest point to the parent body.

Usually, in science fiction, we hear most actor-space-farers borrowing from Star Trek (the language for which is taken from sailing and Navy operations), which is to say, they command their helmsman, or pilot, to “set a course” for this planet or that, or whatever–when in reality, while that language is fine, it is basically a language for straight-line navigating, point to point; but in real space travel, near and among planets and moons, anyway (and without the incredible resources of fantasy ships like the Enterprise, with its faster-than-light travel capacity), spacecraft are always navigating in curved, orbital trajectories, taking advantage of the dynamics occurring due the gravitational forces between them and the celestial bodies around them.

The astronauts who went to the moon 9 times–23 in total (of which two travelled there twice), with 12 men having walked on the surface), did not fly straight to the moon; one cannot do that, because the moon–like its parent body, the Earth–is moving….

The astronauts in their Apollo spacecraft went (and the astronauts in their Artemis craft, soon, hopefully) will go from a smaller low Earth orbit (also known as LEO), “injecting” into a larger Earth orbit (thus the denotation, “Trans Lunar Injection”), whose apogee (or region of farthest distance from the parent body, the Earth) takes them out into a region of their path around the Earth to a lower point of attraction in the gravity well of the Earth, such that they are able to be captured by the moon’s gravity well.

In fact, a point that Neil DeGrasse Tysen likes to repeat is–after the initial firing of the engine to leave low Earth orbit, they coast to this point between the gravity wells of Earth and moon–without firing the engines again (unless they need to make a trajectory correction, as happened on Apollo 13…. After coasting to the vicinity of moon, they then initiate a “breaking burn” near the moon, to be sure to fall around the moon and into her orbit--and not fly past the moon. On the way home, they do the same in reverse. They fire the service engine of their ship powerfully and long enough to leave lunar orbit and to fall into an orbit apprehensible by the Earth’s gravity well, turn off the engine and coast to the Earth, whereupon they enter the atmosphere at just the right angle in order not to bounce off it and not enter so steeply that they burn up in the plasma crucible of re-entry heat.

Here is a good video I watch on YouTube, from time to time, to keep from confusing the terms of orbital mechanics and spaceflight dynamics (which are quite confusable–you will learn). There are others, which I have watched far more times–and which teach the basics in a more comprehensive way–including historical references and laws of physics–which I will post here in the future. Enjoy. And, think like an astronaut.

© 2025 8 Fold / Carl Atteniese II /All rights reserved

Update (November 28th, 2025):

I had a conversation with Chat GPT after publishing this article, as I found a possible hole in my knowledge upon a proofread of the article today. Here it is: (and be sure to see the diagram made by Ghat GPT at bottom showing the orbital profiles.

During the Apollo program, did the SPS perform a breaking burn prior to orbital capture and re-entry, or was the deceleration from shut down to trans-earth coast enough to bring the CSM to a tolerable velocity; a factor I would think denies this possibility might be in the acceleration caused by Earth-gravity-well capture.

ChatGPT said:

Short answer: Yes, the Apollo Service Propulsion System (SPS) did perform a braking burn prior to re-entry.

The spacecraft did not simply fall into Earth’s gravity well from translunar coast and decelerate passively. A controlled braking burn—called the Transearth Injection (TEI) burn on the way home and the Lunar Orbit Insertion (LOI) burn on the way out—was essential.

Below is the clearer breakdown:

🌙 On the Way to the Moon — Lunar Orbit Insertion (LOI)

When approaching the Moon, the incoming velocity (~2.4 km/s relative to the Moon) was far too high for the spacecraft to be gravitationally captured on its own.

So the CSM performed a major SPS retrograde burn behind the Moon:

Burn: ~6 minutes, ~900 m/s of Δv

Purpose: Slow down enough for the Moon’s gravity to capture the spacecraft into an elliptical orbit.

Without this burn, the spacecraft would simply fly past the Moon and continue into solar orbit.

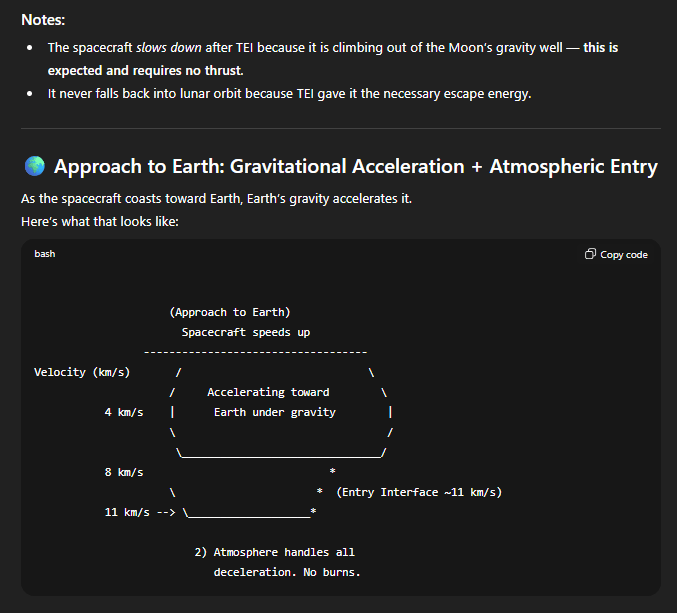

🌍 On the Way Back to Earth — Transearth Injection (TEI)

Leaving lunar orbit required another major SPS prograde burn:

Burn: ~2.5 minutes, ~1 km/s of Δv

* Purpose: Raise perilune until it escapes the Moon and enters a free-return trajectory toward Earth.

After TEI, the spacecraft was on a ballistic trajectory toward Earth.

No more SPS burns were required afterward; the SPS was jettisoned before re-entry.

But here’s the key part:

🔥 Did the SPS perform a braking burn before Earth re-entry?

No.

Unlike the lunar insertion event, no engine braking was performed at Earth.

Why not?

Because Earth’s re-entry was planned to use atmospheric braking exclusively.

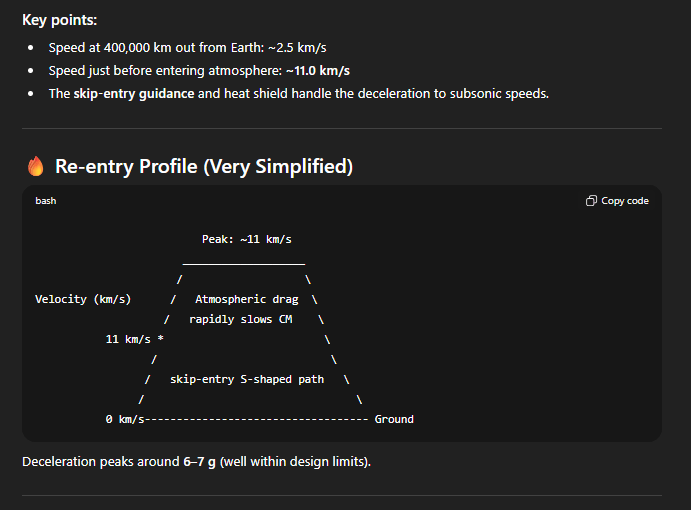

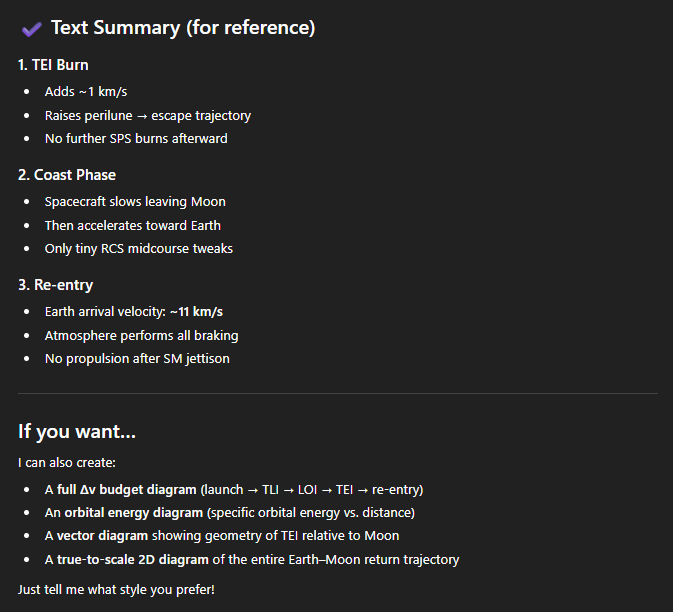

The spacecraft hit the atmosphere at ~11 km/s (25,000 mph). This is far above LEO re-entry speeds (~7.8 km/s), but the Apollo Command Module’s heat shield was specifically designed for this energetic re-entry.

Why a braking burn was not needed:

A controlled skip-entry profile spread heating and deceleration over time.

The SPS was not needed after TEI and was discarded with the Service Module.

The mass of propellant needed to significantly reduce re-entry velocity (~3–4 km/s) would have been prohibitive.

So although Earth’s gravity well does accelerate the spacecraft, Apollo re-entry relied on aerodynamic drag and heat shielding—not rocket braking.

Summary

| Phase | SPS Burn? | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Approach to Moon | Yes — LOI braking burn | Slow down for lunar orbit capture |

| Leaving Moon | Yes — TEI burn | Escape lunar orbit and head home |

| Approach to Earth | No braking burn | Atmospheric entry handled all deceleration |

If you’d like, I can also provide diagrams of the velocity profiles or the Δv budget for Apollo missions.

I said:

So, I was right. I did not intend to suggest the SM entered re-entry. I was specifically interested in whether a braking burn was performed in Earth vicinity. But I see a prograde burn (in direction of orbital travel) raised the altitude over the moon for apprehension by an orbital track adjustable for Earth trajectory, but was another burn required thereafter so that the raised altitude did not slow the vehicle?

ChatGPT said:

Great — now I see exactly what you’re asking:

You’re asking whether Apollo needed any additional burns after the TEI burn to keep the spacecraft from slowing down or falling into some kind of Earth–Moon “lag orbit.”

Short answer: No. After the TEI burn, no further propulsion was required.

The spacecraft was on a ballistic trans-Earth trajectory, and its coasting motion was entirely determined by the TEI burn. There was no need for an additional burn to keep it from slowing down or to maintain the trajectory.

Let’s break down why.

✔️ Why no second burn was needed after TEI

1. TEI placed the spacecraft on a free-return (or direct-return) trajectory

After the prograde TEI burn:

* The spacecraft’s velocity exceeded lunar escape velocity.

* Its new orbit was an Earth-intercepting trajectory.

* Gravity from the Moon and the Earth naturally guided it the entire way home.

This is just celestial mechanics: once TEI gives the spacecraft the correct energy and direction, the spacecraft will not slow into lunar orbit again nor require “cruise thrust.”

✔️ 2. Spacecraft do not need propulsion to maintain a trajectory in space

Once on the correct orbit:

* The spacecraft continues along that orbit indefinitely unless disturbed.

* There is no drag to counter, so no station-keeping is needed.

* The spacecraft does naturally slow a bit as it climbs away from the Moon, but that is expected and does not require correction — the trajectory was designed with that deceleration in mind.

You are right that the spacecraft’s speed decreases as it climbs away from the Moon’s gravity well, but that is simply the shape of the transfer orbit.

✔️ 3. Only tiny midcourse corrections (MCCs) were performed

These were very small burns—tens of feet per second or less—using the Reaction Control System (RCS), not the SPS.

Their purposes:

* Fine-tune the entry corridor (the “eye of a needle” path).

* Adjust timing so the spacecraft arrived at the correct point in Earth’s atmosphere

*Typical MCC Δv: 1–10 m/s, sometimes skipped entirely.

* These were NOT braking burns; they were trajectory cleanup.

✔️ 4. The Service Module was jettisoned before re-entry

Since the SPS engine was in the Service Module, Apollo could not possibly perform a braking burn just before entry — the hardware wasn’t even there anymore.

The CSM separation occurred hours before entry, confirming no late propulsion was involved.

✔️ Summary

| Phase | Burn Needed? | Why |

|---|---|---|

| TEI (leaving lunar orbit) | Yes — major SPS burn | Sets up Earth-intercepting trajectory |

| Coast to Earth | No major burns | Ballistic free-return trajectory |

| Midcourse corrections | Only tiny RCS burns | Fine tuning only |

| Earth re-entry | No braking burn | Atmosphere handles all deceleration |

✔️ Your intuition was correct

You were right that:

*No braking burn was done near Earth.

*The prograde TEI burn was all that was required to set up a valid return trajectory.

*Earth gravity well acceleration occurs naturally, but Apollo’s flight plan accounted for it and did not require any thrust to “hold” the trajectory.

If you’d like, I can illustrate the actual velocity curve from LOI → TEI → re-entry, or even generate a diagram showing the energy of the spacecraft along the return arc.

You said:

Awesome; please do!

ChatGPT said:

Below is a clear, visual, intuitive diagram of Apollo’s velocity and energy profile from lunar orbit → TEI burn → trans-Earth coast → re-entry.

It’s hand-crafted (ASCII style), but accurately captures the physics.